A serra de Sintra - o antigo Monte da Lua que integra a Finisterra, o cabo mais ocidental do continente europeu - foi usada desde os tempos neolíticos como espaço místico de eleição para rituais religiosos, e depois ocupada por ordens religiosas ao longo dos séculos. Desde a Idade Média foi refúgio da corte portuguesa na fuga aos calores estivais, às pestes que periodicamente assolavam a capital, e como local para caçadas. A fama de Sintra, da sua beleza e fascínio vão crescendo e, no século XIX, a vila e a serra entram na esfera do Grand

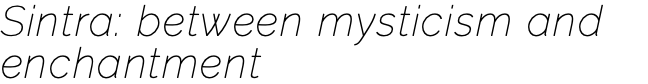

tour europeu. D. Fernando II, rei consorte de D. Maria II, erige o Palácio da Pena no cimo da colina serrana, a partir das ruínas de um antigo mosteiro de monges Jerónimos e, na prossecução do projeto paisagístico envolvente, promove a reflorestação da serra, ao gosto romântico da época.

Esse gosto romântico, de profunda empatia com uma natureza exuberante, une dois aspetos da relação da religião com o património que constituem a base da magia de Sintra, balançando entre as riquezas terrenas e o misticismo do despojamento: a sedução, encantamento e o esplendor dos palácios e quintas da nobreza contrastam, mas ao mesmo completam, a abnegação e expiação espelhadas no Convento dos Capuchos, e é a sua indissociabilidade que dá à paisagem de Sintra um caráter tantas vezes descrito como mágico.

As duas vertentes do êxtase que Sintra induz continuam presentes hoje em dia, entre o gaze de milhares de turistas que se deslumbram com os ricos palácios e as práticas das várias religiões que continuam a usar o espaço da serra como local místico e encantado para os seus rituais.

The mountain of Sintra - the ancient Mount of the Moon, connected to Finisterra, the westernmost headland in the European mainland – was used from Neolithic times as a mystic space for religious rituals, and later occupied by religious orders throughout the centuries. Since the Middle Ages it became, for the Portuguese court, a refuge from the summer heat, from the plagues that from time to time descended on the capital, and a hunting ground. The fame of Sintra, its beauty and fascination, grew and, in the 19th century, both the village and the mountain became part of the European Grand Tour. Ferdinand II, king consort of Mary II, built the Palace of Pena at the top of the hill, over the ruins of an ancient Hieronymite monastery, and, while landscaping the surrounding area, promoted the reforestation, following the romantic taste of the times.

That taste, reflecting a profound sympathy towards a lush nature, united two aspects of the relation between religion and heritage that are the base of the Sintra magic, balanced between earthly wealth and the mysticism of dispossessment: seduction, enchantment, and the splendour of the palaces and manor houses of the nobility contrast, and at the same time compound, the atonement and abnegation mirrored in the Capuchos convent, and the fact that they are inseparable gives the landscape of Sintra a character often described as magic.

The two sides of the pleasure provided by Sintra are still present, amidst the gaze of thousands of tourists enchanted by the rich palaces and the practices of diverse religions that still use the hill as a mystic and enchanted site for their rituals.

O esplendor de Mértola enquanto foi porto fluvial do Mediterrâneo, o que durou desde tempos mais remotos do que o dos romanos até ao período Almóada, com os Impérios Africanos, ainda no século XIII, foi soterrado após a sua conquista sob a égide da Ordem de Santiago.

Em 1876 as cheias que ainda hoje revoltam o rio Guadiana fizeram emergir os primeiros vestígios desse brilho antigo e as camadas de diferentes impérios que se sobrepuseram ao longo de séculos, aparentemente sem grande sobressalto.

Já no século XX, nem a República, e muito menos o Estado Novo, investiram neles: não serviam para o roteiro da sua História monumental e cristã.

No final dos anos 70 do século XX a História havia mudado, e havia que desafiar a sua escrita.

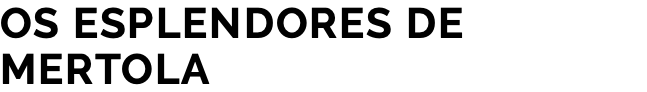

Um projeto de colaboração entre académicos, autarcas e associações cívicas empenha-se na descoberta e investigação arqueológica, no restauro e exibição do património local – predominantemente islâmico – como recurso para o desenvolvimento local de um território durante tanto tempo pobre e abandonado, tanto pelo Estado quanto pela Igreja.

Com o fervor das utopias, escava-se, descobre-se, regista-se, arruma-se e embeleza-se a vila e os seus tesouros, que se exibem em Museus, como relíquias. Faz-se de Mértola uma Vila Museu. Mértola coloca Portugal no Mediterrâneo – numa altura em que o país «entrava para a Europa» – e torna-se a bandeira de uma alegada islamofilia nacional bem segura nas relíquias arqueológicas islâmicas e no casco histórico estudado, preservado, evocativo.

Em 2001 organiza-se o primeiro Festival islâmico. Nos dias do festival de hoje, Mértola continua a engalanar os discursos oficiais, ainda como testemunho da proverbial «tolerância» portuguesa, mas agora sobretudo como forma de distinção cosmopolita e de adesão ao cosmo-optimismo liberal e seus regimes globais do património e do turismo. Vernaculariza-se o discurso académico, aplana-se a religião com o património, confunde-se culto e performance, igrejas com mesquitas e museus. E iluminam-se as relíquias com o brilho mais fulgurante das réplicas.

The splendour of Mértola while a Mediterranean fluvial port, a period which lasted from before the romans to the almohad period, with the african empires of the 13th century, was buried after its conquest under the ruling of the Order of Saint James (Santiago).

In 1876, the floods that even today churn the Guadiana river brought to light the first hints of that ancient radiance and the layers from the different empires that overlapped through the centuries, aparently with no major disturbances.

In the 20th century, neither the Republic, nor (even less) the Estado Novo invested in them: they were of no use for the script of their monumental and christian History.

At the end of the 70’s, History had changed , and its writing had to be challenged.

A collaborative project joining academics, local representatives, and civic associations, commits to the archaeological exploration and research, and to the restoration and displaying of local heritage – mainly islamic – as a resource for local development of a region that has been for a long time poor and forsaken, both by the State and by the Church.

With the feverish zeal of utopia, digs are done, finds happen, all is registered and packed, the village is straightened and embellished, its treasuries are displayed in museums as relics. Mértola turns into a Museum Village. Mértola puts Portugal on the Mediterranean – at a time when the country was “joining Europe” – and becomes the flag for an alleged national islamophilia, well grounded in the islamic archaeological relics and in the historical case studied, preserved, evocative.

In 2001, the first Islamic Festival is organized. In today’s festival occasions, Mértola still brightens the official speeches, still as evidence of the proverbial portuguese “tolerance”, but now mostly as a way of cosmopolitan distinction and of adherence to liberal cosmo-optimism and their global regimes of heritage and tourism. The academic discourse is vernacularized, religion is flattened with heritage, cult and performance become confused, churches, are taken also as mosques and museums. And the relics are lit with the most dazzling brilliance of the replicas.

O bairro da Mouraria, onde viveram confinadas as populações muçulmanas da cidade, desde a conquista cristã em 1147 até à sua expulsão no século XV, é hoje um território culturalmente diversificado. Nas últimas décadas, novas populações habitam, trabalham e circulam neste bairro e as expressões desta transformação cultural e religiosa tornam-se visíveis em espaço público. A Câmara Municipal aprova em 2012 um projeto arquitetónico, a Praça da Mouraria, que incluirá a relocalização de uma mesquita já existente na zona. Todavia por concretizar, esta decisão política é fruto de uma longa negociação entre a “Comunidade Islâmica do Bangladesh” e o poder autárquico da cidade. Em inícios de 2000, os membros desta associação criavam a primeira mesquita. Apesar da pressão da gentrificação, a população do Bangladesh cresce no local. Formam-se associações, nascem novos estabelecimentos comerciais e as celebrações nacionais e religiosas são vividas de forma pública e comunitária. A partir do projeto da Praça, procuramos perceber a relação entre o reconhecimento e a (in)visibilidade do “islão vivido” e os processos de valorização patrimonial associados ao lugar.

The borough of Mouraria, where the city’s Muslim populations lived in confinement after the Christian conquest in 1147 until being expelled in the 15th century, is now a culturally diverse territory. In the last decades, new populations began to dwell, work and circulate in the neighbourhood, and new expressions of this cultural and religious transformations became visible in the public space. In 2012, the City Council approved an architectural project, the Praça da Mouraria (the Moorish square), which will include the relocation of a mosque existing in this area (first created in the early 2000s). Still unfulfilled, this political decision is the result of a long negotiation between the “Islamic Community of Bangladesh” (ICB) and the municipality. Despite the pressure brought by gentrification, the population hailing from Bangladesh has grown significantly in the area. Associations and new commercial endeavours were born, and the celebration of national and religious occasions now takes place in a communal and public way. Based on the Square project, we seek to understand the relationship between recognition and (in)visibility of “lived Islam” and the processes of heritage valuation associated with this specific place.

Antes de 1917, o local em que foi erguido o Santuário de Nossa Senhora de Fátima, a pouco mais de uma centena de quilómetros a norte de Lisboa, era uma zona de pasto nas proximidades de uma pequena aldeia. Tendo já celebrado o seu centenário, Fátima consagra-se, desde há muito, como uma referência mundial da peregrinação católica.

Fátima acolhe quem a visita com uma monumentalidade arquitetónica, exaltada pelo vasto recinto e pelas grandes basílicas que demarcam o território em volta. Contudo, Fátima é também um lugar onde é possível cruzar milhares de memórias vivas, de histórias privadas. Olhada de perto, Fátima é um lugar de intimidade.

Nas experiências dos peregrinos, na sua maioria mulheres, Fátima é simultaneamente um lugar e um momento, onde a dor é falada e feita visível. Aqui as dicotomias ofuscam-se e a memória pessoal dialoga constantemente com a memória coletiva.

Prior to 1917, the place where the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Fátima came to be erected, little more than a hundred kilometres to the north of Lisbon, was just a pasture, close to a small village. Having already celebrated its centennial, Fátima has long stood as a world reference for Catholic pilgrimage.

Fátima welcomes visitors with architectural monumentality, highlighted by the vast precinct and the large basilicas which mark its boundaries. However, Fátima is also a place where thousands of living memories and private stories can be encountered. Seen at close quarters, Fátima is a place of intimacy.

In the experiences of pilgrims, mostly women, Fátima is simultaneously a place and a moment, where grief is spoken and made visible. In here, dichotomies are obscured and personal and collective memories constantly talk to each other.

The Heritagization of Religion and THE Sacralization of Heritage in Contemporary Europe

PROJECT HERILIGION

www.heriligion.eu

Este trabalho é financiado por fundos nacionais através da FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, I.P., no âmbito do projecto UID/ELT/00509/2019